Deng Xiaoping established special economic zones (SEZs) to attract foreign investment, earn foreign profit from exports and create jobs (Pong 2009).

- SEZs offer exemptions from:

- exchange controls

- price controls

- reduced tax rates (Pomeranz 2016)

By 1980 4 SEZs had been established in Shenzhen, Shantou, Xiamen and Zhuhai (Pong, 2009). As of 2014 there were 6 SEZs (denoted by red pins Figure 1), 14 coastal cities (vital to importing raw materials and exporting market goods)(denoted by blue pins on Figure 1) and 363 technology specific industrial parks within China (China’s Special Economic Zone. (n.d.), 2016). 22% of China’s GDP and 60% of China’s exports can be attributed to SEZ production (China’s Special Economic Zone. (n.d.), 2016).

IMPACT OF SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONES

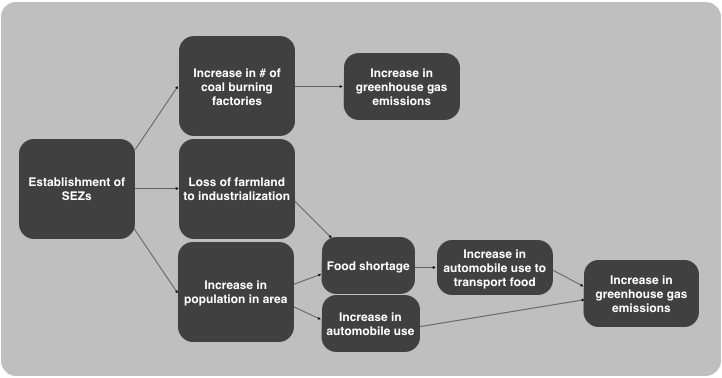

SEZs contribute to air pollution directly by increasing the amount of coal burning factories. China relies predominantly on coal which releases sulfur dioxide when burned (Harris & Udagawa, 2014, p. 619). The establishment of SEZs increased the release of air pollution in China because the zones increased the volume of factories in the country (He, Pan, and Yan, Y., 2012, p.177).

SEZs indirectly contribute to air pollution by increasing the population in the area. As the volume of factories increased, the population in SEZs increased because people migrated for employment (Jiang, 2015, p. 226; Pomeranz 2016). Population increase typically leads to food shortages and increased automobile use (Harris & Udagawa, 2014, p. 619). Since SEZs in China claimed farmland to build infrastructure, food self-sufficiency was reduced; the lack of farmland has forced SEZs to source their food from surrounding provinces (Harris & Udagawa, 2014, 619). Increased food transportation leads to increased carbon dioxide emissions (Meaton 2009).

Citations

Harris, P. G., & Udagawa, C. (2004, August). Defusing the Bombshell? Agenda 21 and Economic Development in China. Review of International Political Economy, 11(3), 618-640. Retrieved September 26, 2016, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4177513

He, C., Pan, F., & Yan, Y. (2012). Is Economic Transition Harmful to China’s Urban Environment? Evidence from Industrial Air Pollution in Chinese Cities. Urban Studies, 49(8), 1767-1790. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

Meaton, J. (2009). Automobiles. In J. B. Callicott & R. Frodeman (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Environmental Ethics and Philosophy (Vol. 1, pp. 84-85). Detroit: Macmillan ReferenceUSA. Retrieved from http://exlibris.colgate.edu:2048/login?url=http://exlibris.colgate.edu:3904/ps/i.dop=GVRL&sw=w&u=nysl_ce_colgul&v=2.1&it=r&id=GAL%7CCX3234100036&asid=a259859a07f78bdce70a74b1178e98b5

Pomeranz, K. (2006). Special Economic Zones (SEZS). In J. J. McCusker (Ed.), History

of World Trade Since 1450 (Vol. 2, pp. 706-708). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&sw=w&u=nysl_ce_col gul&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CCX3447600388&asid=cd06bc7dd04f1 eb204ab27870aa2ac5c

Special Economic Zones. (2009). In D. Pong (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Modern China (Vol. 3, pp. 475-479). Detroit: Charles Scribner’s Sons. Retrieved from http://exlibris.colgate.edu:2048/login?url=http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&sw=w&u=nysl_ce_colgul&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CCX1837900789&asid=fd5e5970504adee2435a4c58fc8df4b8