The main environmental consequences due to increased tourism, lack of policy, and poor monitoring at Zhangjiajie National Forest Park (ZNFP) include:

- Destruction of Soil and Vegetation

- Tree Vandalism

- Air and Groundwater Pollution

- Loss of Biodiversity

Click on the links to learn more information.

Destruction of Soil and Vegetation

Soil and vegetation in the area are vulnerable to destruction, stomping and overuse by visitors and vehicles. This is especially true in high-traffic areas. Trampling by tourists and cars has potential negative effects on soil moisture, the amount of organic matter found in the soil, and it can also lead to the formation of valleys. This process of destruction begins when the leaves on top of the soil are displaced and the top humus layers are destroyed (Shi, Li, & Deng, 2007).

A study done on the vegetation in ZNFP found that high-traffic areas had substantially worse vegetation health than unpopular areas. One example of degradation caused by tourists was found in a popular area called “Treasure Box for Celestial Books” (Shi, Li, & Deng, 2002).

Researchers found that it had lost almost all of its vegetation biodiversity (only one shrub species was found), while a largely untouched area of ZNFP had 36 species. One possible solution proposed by the researchers was to encourage tourists to explore other parts of the already developed park to limit foot traffic in degradated areas.

Tree Vandalism

Trees along trail paths in ZNFP are vulnerable to tree scaring and carving caused by tourist activity in the area. The closer the trees are to the hiking paths, the more likely they are to show signs of scarring (Zhong, Deng, & Xiang, 2007).

One survey done by environmental scientists found that easily accessible trees suffered on average 50 to 100 nicks. The nicks were far more common on smooth bark trees on the side the trunk facing the trails. While the nicking of the trees has mostly just aesthetic consequences, on occasion tourists will go off the trails to scar the trees. This leads to increased destruction of soil and vegetation (Shi, Li, & Deng, 2002).

Air and Groundwater Pollution

As the number of tourists visiting ZNFP rose, so too did the desire for commercialization and lodging. This can be seen especially in the hospitality sector, where the number of beds in the park rose from 4020 in 1990 to 8585 in 1999. Since 1999, warnings and action by UNESCO and IUCN led to a decrease to 5005 beds as of 2004. Nonetheless, consequences to the air and groundwater quality as a result of commercialization still exist (Zhong, Dong, & Ziang, 2007).

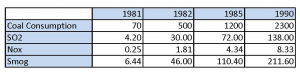

According to Shi (2005) (as cited in Zhong, Dong, & Ziang, 2007), the amount of polluting sources found jumped drastically from 1981 to 1998 in three major locations of the park. As shown in the chart below, the main pollutants caused by increased coal consumption are SO2, NOx, and smog (Zhong, Dong, & Ziang, 2007). Looking at smog specifically, the amount of smog jumped from 6.44 tons in 1981 to 561.20 tons in 1998. See more details below in Figure 4. The increase in smog not only causes respiratory and health issues for humans and animals, but it can also lead to adverse effects in crops, trees, and plants (Ifelebuegu, 2013).

The commercialization of ZNFP has also caused problems with water quality, since the hotels in the area commonly dispose of their sewage and human waste in the park. In 2002, close to 700,000 tons of un-purified sewage was released into nearby streams. Although the park built a water treatment center in 2005, one park guide was quoted saying he still refuses to drink the water like he once did as a child (Zhong, Dong, & Ziang, 2007).

Loss of Biodiversity

Tourism and commercialization has also led to a vast decrease in the variety of flora and fauna found in the park. Activities such as constructing roads and paths, logging, designing gardens, and increased tourist activity has created issues including:

- changed integrity of ecosystems

- inhibited and slowed migratory patterns of animals

- decreased diffusion of plant seeds

- fragmented habitats

(Zhong, Deng, & Xiang, 2007)

All of the above consequences contribute to loss of biodiversity. Biodiversity, or the “variety of living organisms”, is often associated with a healthy ecosystem (Smith, 2011). In terms of mammals, the park has seen a noticeable decrease in the population sizes of red dogs, musk deer, gorals, Asiatic black bears, clouded leopards, and rhesus monkeys. Species like the masked palm civet have actually gone extinct within the park. The loss of these mammal species, along with the destruction of soil and vegetation, could lead to ecosystem instability within ZNFP (Zhong, Deng, & Xiang, 2007)

Click here to continue on to learn about Issues of Power and Privilege in ZNFP.

Citations:

Chensiyuan. (2012). Five Finger Peak [Photograph]. Wikimedia. Retrieved December 6, 2016 from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/62/1_zhangjiajie_huangshizhai_wulingyuan_panorama_2012.jpg/1280px-1_zhangjiajie_huangshizhai_wulingyuan_panorama_2012.jpg

Deng, J., Qiang, S., Vy’alker, G. J., & Zhang,Y. (2003). Assessment on and perception of visitors’ environmental impacts of nature tourism: A case study of Zhang¡iajie National Forest Park, China. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, I l(6),529-547. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1 .1.600.2534&rep=¡ep1&,1 ype=pdf

[Ed_davad]. (2010). Tree Carving [Photograph]. Pixabay. Retrieved December 6, 2016 from https://pixabay.com/p-740334/?no_redirect

[Global Panorama]. (2014). Air Pollution in China [Photograph]. Flickr. Retrieved December 6, 2016 from https://www.flickr.com/photos/121483302@N02/15489395937

Ifelebuegu, A. O. (2013). Smog. In K. B. Penuel, M. Statler, & R. Hagen (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Crisis Management (Vol. 2, pp. 882-884). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Reference. Retrieved from http://exlibris.colgate.edu:2048/login?url=http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&sw=w&u=nysl_ce_colgul&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CCX3718900320&asid=5e05ee95aa2ac91dbf74c6e5a07994ff

[Kabbachi]. (2010). Masked Palm Civet – 02 [Photograph]. Flickr. Retrieved December 6, 2016 from https://www.flickr.com/photos/kabacchi/5028701905

Shi, Q., Li, C., & Deng, J. (2002). Assessment of impacts of visitors’ activities on vegetation in Zhangjiaje National Forest Park. Journal of Foresty Research, 1 3(2), 137 -140. Retrieved from Colgate Library.

Smith, D. I. (2011). Biodiversity Loss/Species Extinction. In K. Wehr & P. Robbins (Eds.), The SAGE Reference Series on Green Society: Toward a Sustainable Future. Green Culture: An A-to-Z Guide (pp. 47-52). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Reference. Retrieved from http://exlibris.colgate.edu:2048/login?url=http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&sw=w&u=nysl_ce_colgul&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CCX1560000027&asid=3232bd3ad5d34ca90873b919f78b8a69

Zhong, L., Dang, J., & Ziang, B. (2007). Tourism development and the tourism area lifecycle model: A case study of Zhangjiajie National Forest Park, China. Tourism Management, 1(16). doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.10.002