Table of Contents

- History of National Forest Parks in China

- Scientific and Geographical Context

- NFP Policy Initiatives

- Demographics of Key Players in NFP Development

History of National Forest Parks in China

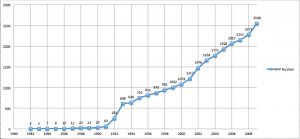

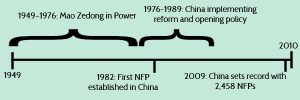

In 1982 following a nation-wide forest tourism symposium, the first National Forest Park (NFP) was created in Zhangjiajie, Hunan Province. By 2009, China had established a record-breaking 2,458 NFPs. You can see the staggering growth in Figure 1 below. Nonetheless, China’s history is one filled many environmental struggles, particularly with deforestation and maintaing forest cover (Chen & Nakama, 2013).

Prior to 1982

Even as early as 300 BCE, agricultural pursuits and logging for energy needs had already caused a major loss of China’s northern forests. Fast-forwarding to the 1800’s, China was “so deforested that it was facing a pre-modern energy crisis” (Marks, 2012, p.6).

Between 1958 and 1976, Communist leader Mao Zedong launched a series of economic policies focused on spurring economic and industrial growth. The economic plans left forests largely susceptible to logging, pollution, and deforestation for the development of infrastructure and agriculture (Economy, 2010, p. 53).

By 1976, China had started the process of opening its doors to outsiders and was in desperate need of revenue by means of domestic and international tourism (Wen, 1997, p. 566).

After 1982

Over 100 years after the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in the United States, the Chinese government decided to look into creating a National Forest Park system. The government realized they could both try and protect the vulnerable forest ecosystems in China, while taking advantage of tourism revenue (Wang et al., 2012).

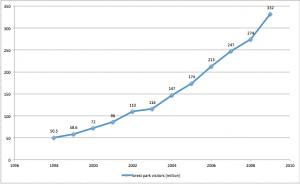

Since the establishment of Zhangjiajie NFP in 1982, the number of NFP’s has skyrocketed as a result of the Reform and “Opening Up” Program. China’s NFP system as of 2009 has reached nearly $3 billion in revenue and averaged 332 million forest park visitors annually (Chen & Nakama, 2013). You can see the growth in visitors after 1982 in Figure 4 below.

Scientific and Geographical Context

China’s Forests

With 175 million ha of forest cover spanning 18.21% of China’s total land in 2005 , China ranks fifth globally in total forest area. Due to weather patterns and imbalances of moisture, most of the forests and therefore NFPs in China are found in Northeastern, Eastern, and Southern China (Chen & Nakama, 2013).

What is a NFP?

According to the Forest Park Management Regulation:

“a national forest park is defined as a specific forest area of scenic forest landscape with intense historic and cultural heritage for the purpose of tourism, recreation, and scientific, cultural, and educational activity” (Forest Park Management Regulation as cited in Chen & Nakama, 2013, p. 286).

Regardless of this definition, China’s NFPs have often been criticized for placing tourism and recreational opportunities over scientific and environmental needs (Wang et al., 2012).

Environmental Consequences of NFPs

Due to the major commercialization of NFPs in China, several environmental consequences and concerns have been noticed including:

- Destruction of Soil and Vegetation

- Tree Vandalism

- Air and Groundwater Pollution

- Loss of Biodiversity

The rate and prevalence of each of these concerns varies from NFP to NFP. For more information about these specific consequences, check out this page.

NFP Policy Initiatives

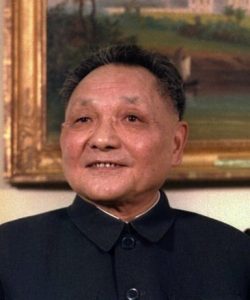

China now has the largest number of NFPs globally, but it was not always this way. In 1991 there were 63 NFPs, but by the year 1993 this number had jumped to 608. This quick growth, created by Deng Xioping’s Reform and “Opening Up” program, jumpstarted the NFP system.

Reform and “Opening Up” Program

Before 1991, China invested little money into the NFP system, mostly due to a lack of funds. Between 1991 and 1993, China decided to invest RMB 13 million (currently close to $2 million) in the construction of hotels, restaurants, and stores in NFPs. One of the main reasons for the investment was a speech in 1992 by China’s leader at the time, Deng Xiaoping, pushing for economic growth at a faster speed (Chen & Nakama, 2013).

The Reform and “Opening Up” Program prioritized domestic tourism and other economic pursuits to generate revenue and financial prosperity. Between 1990 to 1995, the annual domestic rate of tourism increased by 17.62% (Wen, 1997).

Lack of Policy

While a number of Chinese government agencies control the protection and promotion of NFPs, one of the major complaints about ecotourism and NFPs is the lack of policy (Chen & Nakama, 2013). Programs such as the Reform and “Opening Up” encourage the creation of NFPs, but no official NFP legislation has been put in place to mandate monitoring, limit commercialization, or require protection of the natural landscape (Wang et al., 2012).

Demographics of Key Players in NFP Development

There are four key groups necessary to understanding the development and history of National Forest Parks in China:

Tourists

After the economic development of the 1990’s, the expanding middle class earned more vacation time and developed an interest in outdoor activities (Wang et al., 2012). These wealthy, educated tourists flock from urban areas hoping to escape the pollution and take advantage of the pristine air for the weekend (Wang & Buckley, 2010). In 2009, the number of tourists visiting China’s NFPs was estimated to be over 330 million, with only 97% of them domestic(Chen & Nakama, 2013).

Local Villagers

The majority of NFPs restrict the use of the land by villagers, who sometimes rely on the land for their livelihood (Wang et al., 2012, p. 255). Additionally, with tourists often outnumbering the local residence, it is not uncommon for “resources and services [to be] diverted from local communities” (Zhong, Dang, & Ziang, 2007). One of the benefits of NFPs, however, is that generally develop in areas of poverty and have been shown to employ locals lacking professional training and education (Chen & Nakama, 2013).

The Chinese Government

Multiple government agencies, including the Ministry of Culture, Ministry of Water Resources, State Tourism Administration, and Ministry of Environmental Protection often oversee National Forest Parks. All have conflicting goals, and one of the consequences of this conflict of interest is a lack of large-scale legislation (Wang et al., 2012). One proposed solution to solving the issue of NFP exploitation is to have all NFPs be controlled by one government entity (Chen & Nakama, 2013).

The Private Sector

Since NFPs are considered self-funding organizations, or organizations that support themselves through personal revenue, they generally rely on money from mega-wealthy private investors (Wang et al., 2012). One of the many complaints about NFPs is that they place the needs of the private sector and these investors above all else, and in some cases have even profited more from tourism than the government (Chen & Nakama, 2013).

Click here to continue your educational journey and learn about Zhangjiajie National Forest Park, the first National Forest Park established in China.

Citations:

Chen, B., & Nakama, Y. (2013). Thirty years of forest tourism in china. Journal of Forest Research, 18(4), 285-292. doi: 10.1007/s10310-012-0365-y

Dedering. U. (2010). Map Showing the Location of Zhangjiajie National Forest Park [Online Image]. Wikipedia. Retrieved December 6, 2016 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zhangjiajie_National_Forest_Park#/media/File:China_edcp_relief_location_map.jpg

[Deng Xiaoping]. (1979) [Photograph]. Wikimedia. Retrieved December 6, 2016 from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1c/Deng_Xiaoping.jpg

Economy, E. C. (2010). The river runs black: The environmental challenge to China’s future. Ithaca: Cornell university press.

Evans. S. (2004). Agriculture in China [Photograph]. Wikimedia. Retrieved December 6, 2016 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:China_Harvest.jpg

Galindo, C. A. (Photographer). (2014). Zhangjiajie [Photograph]. Flickr. Retrieved December 6, 2016 from https://www.flickr.com/photos/cadampol/17405916911

Marks, R. (2012). China, Its Environment and History. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Chapter 1 and Chapter 2- pp. 1 – 22.

Rolfmueller. (Photographer). (2011). Diaoshuihu Waterfall in the Longwanqun National Forest Park, Huinan County, Jilin, China [Photograph]. Wikimedia. Retrieved December 6, 2016 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Longwanqun_national_forest_park_diaoshuihu_waterfall_2011_07_25.jpg

Takeaway. (2007). Yuanyang hani farmer [Photograph]. Wikipedia. Retrieved December 6, 2016 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agriculture_in_China

Wang, C., & Buckley, R. (2010). Shengtai anquan: Managing tourism and environment in China’s forest parks. Ambio, 39, 451-453. doi: 10.1007/s13280-010-0035-2

Wang, G., Innes, J. L., Wu, S.Vy’., Krzyzanowski, J., Yin, Y., Dai, S., . . . Liu, S. (2012). National park development in China: Conservation or commercialization. Ambio, 41 (3), 247 -261. doi: 10.1007/s13280-011-0194-9

Wen, Z. (1997). China’s domestic tourism: Impetus, development and trends. Tourism Management, I 8(8), 565-57 I. Retrieved from http://www3 .tjcu.edu.cn/wangshangketang/lyxgl/yuedu/ 1 5.pdf

Zhong, L., Dang, J., & Ziang, B. (2007). Tourism development and the tourism area lifecycle model: A case study of Zhangjiajie National Forest Park, China. Tourism Management, 1(16). doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.10.002